As for the aberrations of a shallow optimism, the ground (of English fiction especially) is strewn with their brittle particles as with broken glass

—Henry James, The Art of Fiction

Not every story happens to everybody

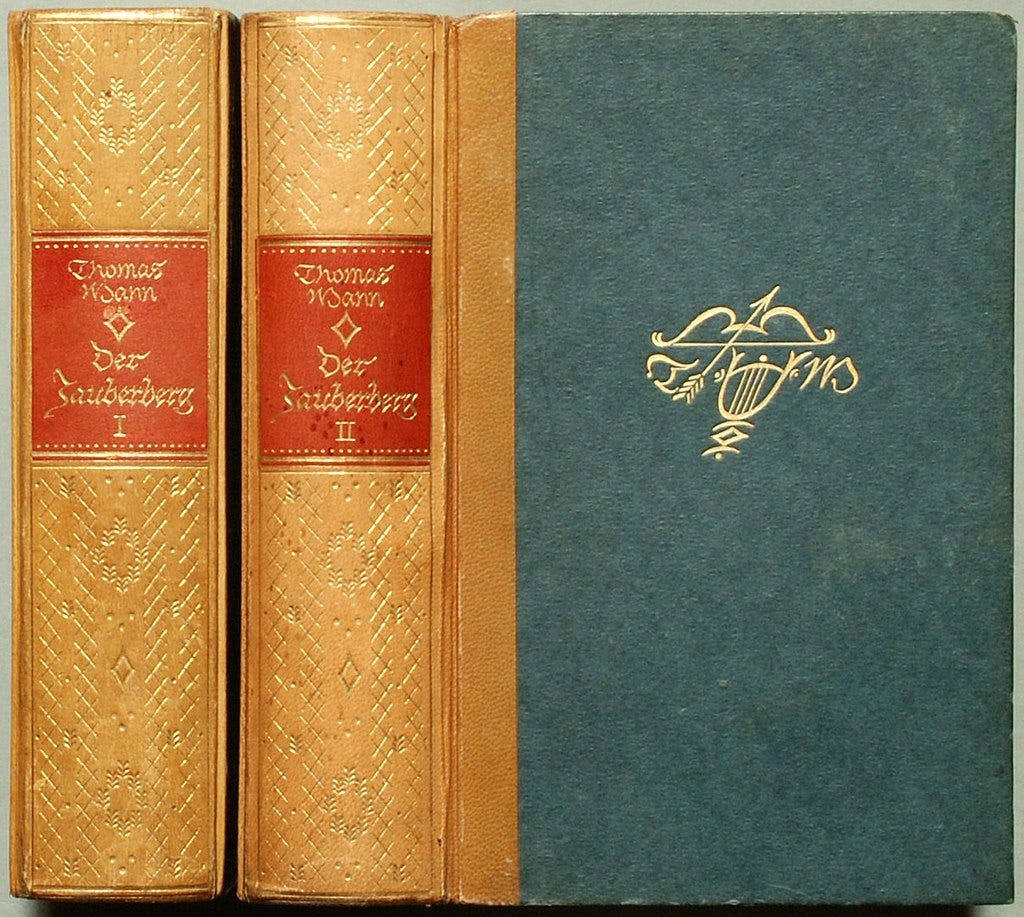

—Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain

I. A minor ethics of reading: or, the bare minimum

This is an essay about health and illness, reading and history, memory and desire. It has two goals: one that is specific and literary-critical, and another informed by philosophy and literary theory, representing my attempt to think about the purposes of literary studies today. I want to consider the status of the German author W. G. Sebald in relation to modernist literature; if like Kafka Sebald has generated a literary adjective (‘Kafkaesque,’ ‘Sebaldian’), then as with Kafka the precise meaning of that adjective remains to be defined. What we take to be characteristic of an influential author’s work is continually up for debate, and so the meanings of ‘Kafkaesque’ and ‘Sebaldian’ will continue to change historically. In the context of multiple current crises—COVID-19, wars, and imminent ecological disaster—I also want to describe what I will provisionally call a minor ethics of reading—after Theodor W. Adorno’s Minima Moralia (1951)—and in particular, how reading can be a way of remembering what we should not forget. This will not be a grand ethical theory of literature but rather a preliminary investigation, as it were, of how reading and remembrance are a part of ethics in the present; though by no means would I want to insist that reading is ‘better’ or more important than other kinds of cultural experience. For theoretical or philosophical guidance I will refer to the thought and writings of Adorno, Henri Bergson, Cathy Caruth, Fredric Jameson, and Hayden White, among others, and in the end I expect this project will amount to a few expectations, stated anew, for deliberately political literary criticism. What I identify as Sebald’s particular formal achievement will illustrate the concerns I have about the roles that memory plays in reading. I understand Sebald to be a belated modernist, in contradistinction to the term ‘late modernism,’ which aims to specifically periodize modernist writing. I also understand reading to be an activity through which we may be able to understand our own belatedness. When we read about the past in fiction or nonfiction we come after the writing of the text and whatever events or experiences it may refer to or represent: we are always late. So reading is a fundamentally belated activity, and anxieties about that situation or predicament have been addressed in literary and philosophical thought from Plato through Derrida—and beyond, to be sure. For the purposes of this essay I have to assume that reading, however belated or deferred, is not yet discredited without pretending that such an assumption needs no justification. If we are always late it does not follow that we are too late to bother attempting to understand—or to not misunderstand. That double-negative may help us to move beyond the feeling that true understanding is impossible, because even if we only approach true understanding asymptotically the positive work to be done along that line would primarily be the work of mitigating or correcting misunderstanding. And not-misunderstanding primarily entails less certainty and more openness on the part of the reader, and indeed something like what Keats called ‘negative capability.’

Given the problems that temporality poses for reading toward understanding, we can begin by considering how reading and memory are intertwined. One influential concept we have received from literary modernism is the distinction between voluntary and involuntary recollection. The first volume of Proust’s novel provides a useful and introductory depiction of the two remembrance-modes in their interplay:

I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. […] a shiver ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. […] I put down the cup and examine my own mind. It alone can discover the truth. But how? What an abyss of uncertainty, whenever the mind feels overtaken by itself; when it, the seeker, is at the same time the dark region through which it must go seeking […] Seek? More than that: create. It is face to face with something which does not yet exist, which it alone can make actual, which it alone can bring into the light of day. (60-61)

Here we find a narrator who is simultaneously ‘seeking’ in memory and re-creating memories through a deliberate attempt at remembrance, and that will become Proust’s literary method.1 From this brief scene stems the entirety of Proust’s novel, but in an obviously artificial sense; half of Swann’s Way (1913), itself only the first volume, will be devoted to a voluntary reconstruction of childhood memories that have apparently been involuntarily recollected. Proust is not simply writing about involuntary memory—he is using that involuntary experience to ground the voluntary construction of what will become, in time, a novel celebrated and feared for its great depth and length: this is what Fredric Jameson calls, in regard to Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924), “form production.”2 The sheer length of Proust’s novel means that the reader’s recollection and forgetting are more conspicuously part of the reading experience than with most (if not all) other novels. And early in Proust’s long project we read his attempt to justify its form, which is in part one of sheer duration—the time represented in the text, and the time it will take to read. To an extent the same is true of Mann’s novel, because just as its protagonist Hans Castorp finds reasons to stay at the Berghof sanatorium for seven years, The Magic Mountain must find reasons for its length in the absence of conventional plot or narrative; in a novel about a protracted stay at an isolated sanatorium the sense that the text’s form is itself ‘filling time’ becomes inextricable from the meaning of the book. In general, and by way of comparison with Proust and Mann, this concept of form production will be important below. Although Sebald is not a writer of monumental verbosity (none of his novels exceeds 300 pages), he does have a form to produce, and one that will call for a certain kind of readerly attention to aberrations or anomalies in narrativity and time.

Proust’s production of a literary form that could potentially fulfill the possibilities of involuntary recollection is indebted to the philosophy of Henri Bergson. We should note that as Bergson writes in Matter and Memory (1896) “there is no perception which is not full of memories.” Moreover, as Henri Bergson and British Modernism (1996) describes, Bergson generally examines how “memory allows awareness of perceptions; it is memory that permits the existence of consciousness” (Gillies 15). And following Bergson, Adorno writes in Minima Moralia that: “Memories cannot be conserved in drawers and pigeon-holes; in them the past is indissolubly woven into the present” (166).3 So memory is foundational for consciousness (as consciousness of self) because memories constitute the lived persistence of the subject—however singular or plural, fragmented or whole that subject may find itself to be—in what Bergson calls la durée, the free-flowing experience of being in time which we habitually construct in spatial, measured terms as l’entendu, or ‘clock time,’ in order to gain some control over time’s flux. And memory is fundamental to self-conscious perception because in perception memories are brought into relation with what is not memory: what is objective, what is other, what is ‘out there.’ Given that reading is a peculiar kind of perception, we can draw back from the complexities of Bergson’s thought to note that as readers we are all belated in two complementary senses. We come to a text after it has happened—that is, after it has been written, and thus necessarily after whatever events to which it may refer. We also perceive a text through our own memories (of reading and of non-reading), and thereby belatedly encounter, in reading, ourselves as reading beings, for we are always ‘reading’ or interpreting our perceptions via memory. Reading can help us build up ideas of selfhood, and of selfhood in relation to others, especially when immediate experience fails to provide what we need or desire: “through aesthetic experience both artist and audience are joined in a common activity—the rediscovery of the emotions, perceptions, and impressions that prompted the fashioning of art” (Gillies 20). Not every narrative happens to everyone, but when we approach a work of art we are all more like artists, or narrators, than we tend to realize. Thus when we read Proust we are invited to rediscover, or voluntarily remember involuntarily, our own experiences, and in Proust this includes experiences of reading, and even of desiring to write. What remains problematic for this view of reading and perception is the negative side of belatedness: what happens when we may not want to reconstruct what preceded the present moment, be it our own or that of others. Understanding the past that we have inherited can often be an inconvenient, painful, unfashionable, or unpopular task, and one all too easy to avoid.

This is where both ethics and politics conspicuously enter into this modernist-informed account of reading and memory, and where I want to focus on the thought of Theodor Adorno, one of Sebald’s major influences.4 In an essay first delivered as a lecture in Wiesbaden in 1959, titled “The Meaning of Working through the Past,” Adorno addresses a societal reluctance to adequately ‘work through’ or move beyond Germany’s recent history: “One wants to break free of the past: rightly, because nothing at all can live in its shadow […]; wrongly, because the past that one would like to evade is still very much alive” (3). Postwar Germany needs to be truly post-war, post-Holocaust, in order for life to be possible, but a failure to truly ‘work through’ that past, and a preference for evasion have meant that the conditions for that past linger in a supposedly ‘denazified’ Germany; Sebald would later call this a “conspiracy of silence” (“Ghost Hunter” 44). This is a familiar predicament for citizens of any country with a past they would prefer to forget, and for Adorno the situation in Germany gives ‘working through the past’ a privileged exigency: “We are all […] familiar with the readiness to deny or minimize what happened […] The idiocy of all this is truly a sign of something that psychologically has not been mastered, a wound, although the idea of wounds would be rather more appropriate for the victims” (5). We should note that by introducing this notion of the “wound” as what is not ‘psychologically mastered’ Adorno anticipates the claims of what will, toward the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first, be known as trauma theory, though to Adorno’s credit he does not let this point stymie or delay his political claim. As in Minima Moralia and other writings, his writing marks for remembrance the subjective difficulty of thinking about the past at present.5 And as Richard White has recently suggested, Minima Moralia is “a gift offered to the reader who does not know how to think or to live anymore” (14). These are among the most difficult and persistent problems of the present—that is, our present.

In the lecture on “Working Through” Adorno goes on to address a notion that is now fairly common, and which has become relevant to Sebald’s reception: that of Germany’s guilt complex, or the related sense of ‘survivor’s guilt.’ But as Adorno notes, “talk of a guilt complex has something untruthful to it.” He clarifies this by asking, rhetorically enough: “is guilt itself perhaps merely a complex, and bearing the burden of the past pathological, whereas the healthy and realistic person is fully absorbed in the present and its practical goals?” (5). In other words the postwar status quo does not simply prefer not to think about the recent past and its horrors—it understands all serious engagement with that past to be ‘unhealthy.’ This has consequences for the victims of Germany’s history: “The murdered are to be cheated out of the single remaining thing that our powerlessness can offer them: remembrance” (5). Adorno is not primarily seen as a philosopher of memory, but remembrance is nevertheless a major concern throughout his work. In fact that last quotation from his 1959 lecture recalls something he wrote in an essay on Mahler, circa 1936:

Remembrance combs the hair of the helpless, brings sustenance to the shattered mouth, watches over the sleep of those who will not awaken. Just as they [the dead] are defenselessly abandoned to our remembrance, our remembrance is the only assistance left to them. They pass away into remembrance, and if each person who dies resembles one who has been murdered by the living, then the person who dies also resembles one who must be saved by the living, without knowing whether they will ever succeed. The rescue of the possible but not yet existent is the goal of remembrance. (“Marginalia on Mahler,” pp. 79-80).

At this point we can recognize that Adorno’s writing is not simply or strictly theoretical: he is a literary stylist no less than Proust or Sebald, and his writing tends to provocatively exaggerate—here in order to push remembrance and its necessity beyond sentimentality and toward resistance. One thing Adorno is resisting in his writing (to the extent that we can generalize about his work) is the tendency of ‘objective’ normality to move past without working through, to run-over the victims of the recent past instead of rescuing them. That such a rescue may fail does not negate its urgency, and this way of thinking and writing is a potent corrective to inaction borne of apathy or despair. It is also remarkable that this passage on remembrance should appear at the beginning of an essay otherwise closely focused on musicology, and moreover one written prior to the full-scale industrial murder carried out by the Nazis and their co-conspirators. Living after the Holocaust intensified Adorno’s conviction that aesthetics and politics were not only inseparable but also intractable in their false separation: aesthetic writing is to be political, and political writing is to be aesthetic.6And his point in that passage (an impressively poignant one) is that what our remembrance can do for the dead and the murdered is very little, and indeed almost nothing.

This is an Adornian minor ethics, or more precisely the beginning of a negative ethics: not to forget and not to misunderstand, because those two categories of error betray the past and menace the future. Or, as Adorno has it in his essay on “Commitment” in literature: “The abundance of real suffering permits no forgetting” (252). That these imperatives may seem relatively straightforward obviously does not mitigate their difficulty or negate their urgency, as belated as it may be. But then the notion of a belated urgency may be apt for a moment vexed with the question of whether it is modern, modernist, postmodern, postmodernist, or post-postmodern. And to the extent that the present moment seems to be an ever more intense network of crises, we may find that what is urgent today was, paradoxically enough, no less urgent in the past and not, as we tend to assume, melodramatically ‘more urgent’ today. To be sure, it really will be harder to mitigate the ravages of climate change the longer we delay mitigation, but that should not grant us an ever-more exquisitely fatalistic lament. We should begin by recognizing belatedness as the position from which we must begin, instead of merely regretting this.

But the difficulty of actually doing anything oriented toward the past or the future in the present bears further consideration. In Minima Moralia, in a passage dated during WWII, Adorno writes: “Life has changed into a timeless succession of shocks, interspaced with empty, paralysed intervals. But nothing, perhaps, is more ominous for the future than the fact that, quite literally, these things will soon be past thinking on, for each trauma of the returning combatants, each shock not inwardly absorbed, is a ferment of future destruction” (54). When the past—or the present—is traumatic it is more urgently necessary that it be ‘worked through’ to whatever extent is possible. The greatest impediment to that healing process is what passes for normality but should be seen as virtual amnesia: “The idea that after this war life will continue ‘normally’ […] is idiotic. […] Normality is death” (55-6). The abnormal reveals the falsity of what we may be in the habit of taking to be normal. And the wounded, far from being aberrations in a normal order, testify to the lethality of normality: they remember this and remind us of it (a burden in its own right, to be sure). Accordingly, Adorno has a clear political conclusion about how, exactly, the past should be worked-through: “The past will have been worked through only when the causes of what happened have been eliminated. Only because the causes continue to exist does the captivating spell of the past remain to this day unbroken” (“Working Through” 18). Working through the past is identical with working for the future; thinking about the past will never be enough. Still, we should also linger awhile with what Adorno calls “the captivating spell of the past,” and here we can turn to trauma theory.

Trauma theory is intensely controversial today (for an academic discourse, anyway), so I make it a part of this essay with some trepidation. By no means would I like to intervene in trauma theory or trauma studies. But at this point we are considering how remembrance is always too late, not clearly possible, and nevertheless necessary, and trauma is a closely relevant concept. The reader who tries to practice remembrance by reading texts that refer, fictionally or non-fictionally, to events that were experienced as traumatic encounters therein what cannot be fully or finally understood, and what nevertheless should be understood—even if the content of that understanding is negative. This is to say that reading about trauma is in part oriented toward understanding what we cannot quite understand, or understanding the limits of understanding. Now, as I see it much of trauma theory’s controversy arises in reaction to the excesses of its theorists, or to a few particular insights into trauma, language, referentiality, and history being expanded unnecessarily into a ‘theory’ proper and tenuously related to empirical science.7 This controversy in all its detail cannot concern us here. Nevertheless, I have found Cathy Caruth’s influential monograph Unclaimed Experience (1996) useful in my attempts to understand both reading-as-remembrance in general and W. G. Sebald in particular. As Caruth claims in her discussion of Freud, both psychoanalysis and literature are “interested in the complex relation between knowing and not knowing” (3). It seems safe to say that such a relation must be at play in the practice of reading precisely because a text offers the possibility of knowing, not its guarantee, regardless of the question of fictionality. And frankly it is in terms of textual—or simply mediated—transmission that I find Caruth’s work helpful. Insofar as we exist in a present moment that follows a past, we come after histories that we ought to try to understand even as we acknowledge that they are beyond understanding. But this is why the novel and the treatise are not interchangeable: some problems, some experiences cannot be written directly. Fiction does not untruth make.

In particular, trauma theory can help clarify the experience of belatedness, even though that experience is more familiar than we may assume. As Robert Eaglestone notes, “Freud’s idea of ‘Nachträglichkeit’ [‘afterwardness’] is theoretically complex but—oddly—experientially easy,” (12) because we all experience the present as after the past from which our constitutive memories arose. The present is always (yes, already) afterward. And Caruth writes that trauma is locatable “in the way that its very unassimilated nature—the way it was precisely not known in the first instance—returns to haunt the survivor later on” (4). My priority is to think about how non-survivors who come after a trauma—who ‘survive’ the past in another sense—are in a secondary, lesser, and nevertheless compelling way haunted by the traumas others live with. Not for nothing do we generally recognize (or claim to recognize) that we ought to understand, for instance, the genocidal extermination of Indigenous peoples in what is now North America, the horrors of trench warfare in WWI, or the unimaginable crimes which we simply refer to in aggregate as the Holocaust. Those and so many other histories are crises of both the past and the present, and therefore potentially of the future. And in Caruth’s words, these violent histories “simultaneously [defy] and [demand] our witness,” so the question of how we should live after them is a question that will have to “be spoken in a language that is always somehow literary: a language that defies, even as it claims, our understanding” (5). This does not entail a frightening relativistic future of post-historical post-truth. We know that a literary text is never conclusively interpreted, so why are we afraid to admit that we will never be finished understanding history? From neither recognition necessarily follows a chaotic free-for-all of baseless meaning, subjectivism, and ambiguity. And as will become clearer below, a presupposed absolute distinction between literature and historiography is untenable. So we may find that literature is, after all, a valid means of attempting to understand the past and our belated relation to it. With this theoretical orientation—or simply, with a certain contention that reading and remembrance are essential at the present—in mind, we can consider what exactly W. G. Sebald and his work mean today.

II. ‘The Sebaldian’ today

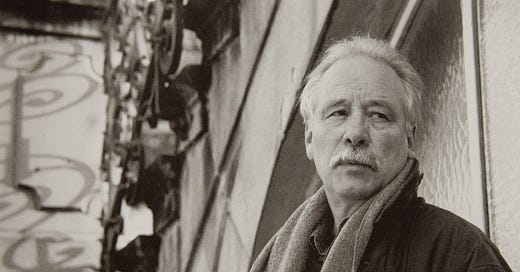

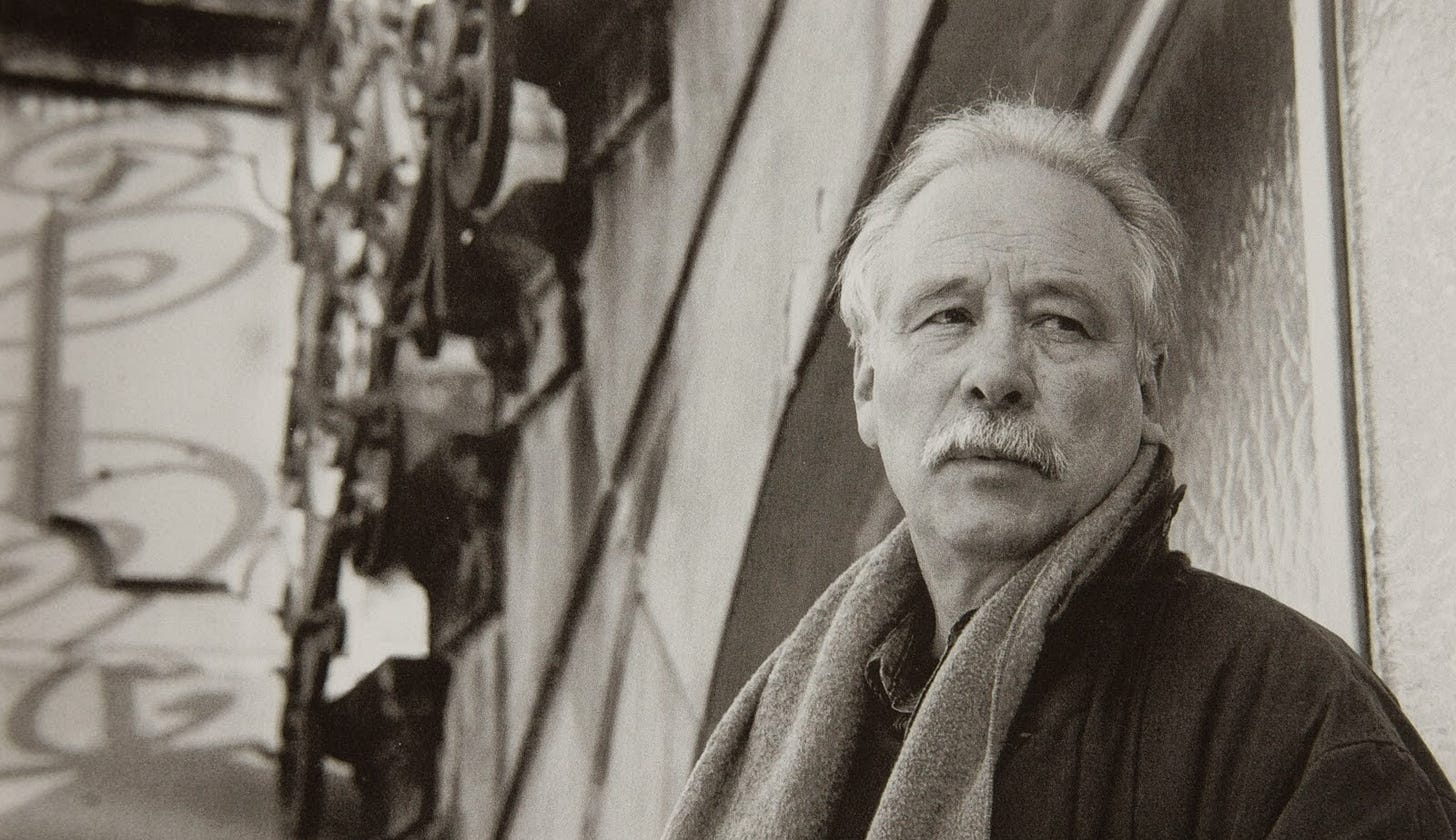

Like trauma theory Sebald has lately become controversial, though in his case we will have to address the controversy directly.8 The German author, who was born in 1944 and died in 2001, is the subject of an unauthorized biography by Carole Angier, titled Speak, Silence: In Search of W. G. Sebald (2021). It is in public-facing reviews of this book, not in academic scholarship, that Sebald is most prominent and problematic at this moment.9 The novelist Ben Lerner begins his review of Angier with a series of Sebald’s lies as reported in the biography, which range from the “funny” to the “disconcerting,” in Lerner’s words, and culminate in Sebald’s misrepresentation of his own correspondence with Theodor Adorno (par. 1). We are informed that in his master’s thesis Sebald cited two letters received from Adorno, whereas Adorno actually sent him just one. Lerner goes on to describe Sebald’s use of sources without attribution and his ‘misrepresentations’ of “the real people behind his fictions” (par. 3). I will set aside this disquieting problem, temporarily, in order to note what Lerner asks of Sebald today: “Does Sebald’s style reinscribe a sense of human possibility while keeping vigil with the dead? Or does it merely aestheticize catastrophe?” (par. 13). This framing of Sebald’s literary worth is not particularly useful. It reduces his work to either a hollow performance of melancholy humanism or else a perverse example of literature taking pleasure in the representation of atrocity. Ultimately neither view gives us an adequate understanding of the significance of Sebald’s writing. But Lerner himself eventually admits that these questions are actually raised by Sebald’s writing: “Sebald’s work has been important to me not because it solves any of these problems but because it makes them felt. To take him seriously is to find his books unsettling” (par. 14). As I will attempt to demonstrate, Sebald’s work answers those problems precisely by ‘making them felt’ in peculiar and indirect ways. To make them felt is itself an answer, as Adorno’s work on normality and ‘working through the past’ has already indicated to us.

We are all capable of recognizing that it is difficult to do justice to the past and to the memories of others, and the phrase ‘do justice’ is probably not very helpful, thanks to its vagueness. What would justice itself do for victims of past violence if that violence is shortly forgotten and thus allowed to recur? Remembrance should be unsettling. Ultimately Lerner seems to be unsettled more by Sebald’s person—or rather, by his unauthorized biography—than by the texts themselves, and that might serve as an emblem for the confusion and distraction sown by Angier. I would suggest that the expectation that Sebald’s life will illuminate his work probably follows from misreadings of that work itself. I insist, following Barthes, that the author is dead, and in this case the author’s life—as written by others—is a text of far less interest than the author’s aesthetic productions. The single most important life-experience of Sebald’s for our understanding of his position as a writer is one he shared with so many Germans, and indeed with people the world over: afterwardness or belatedness. This historical belatedness, a persistent consciousness of oneself as living-after, is echoed in the experience of every reader who comes to a text and perceives, consciously or unconsciously, that they are late in doing so. Today the meaning of Sebald’s books is to be found in the reader, not the writer, and I will try to show how this is already modelled by the books themselves.

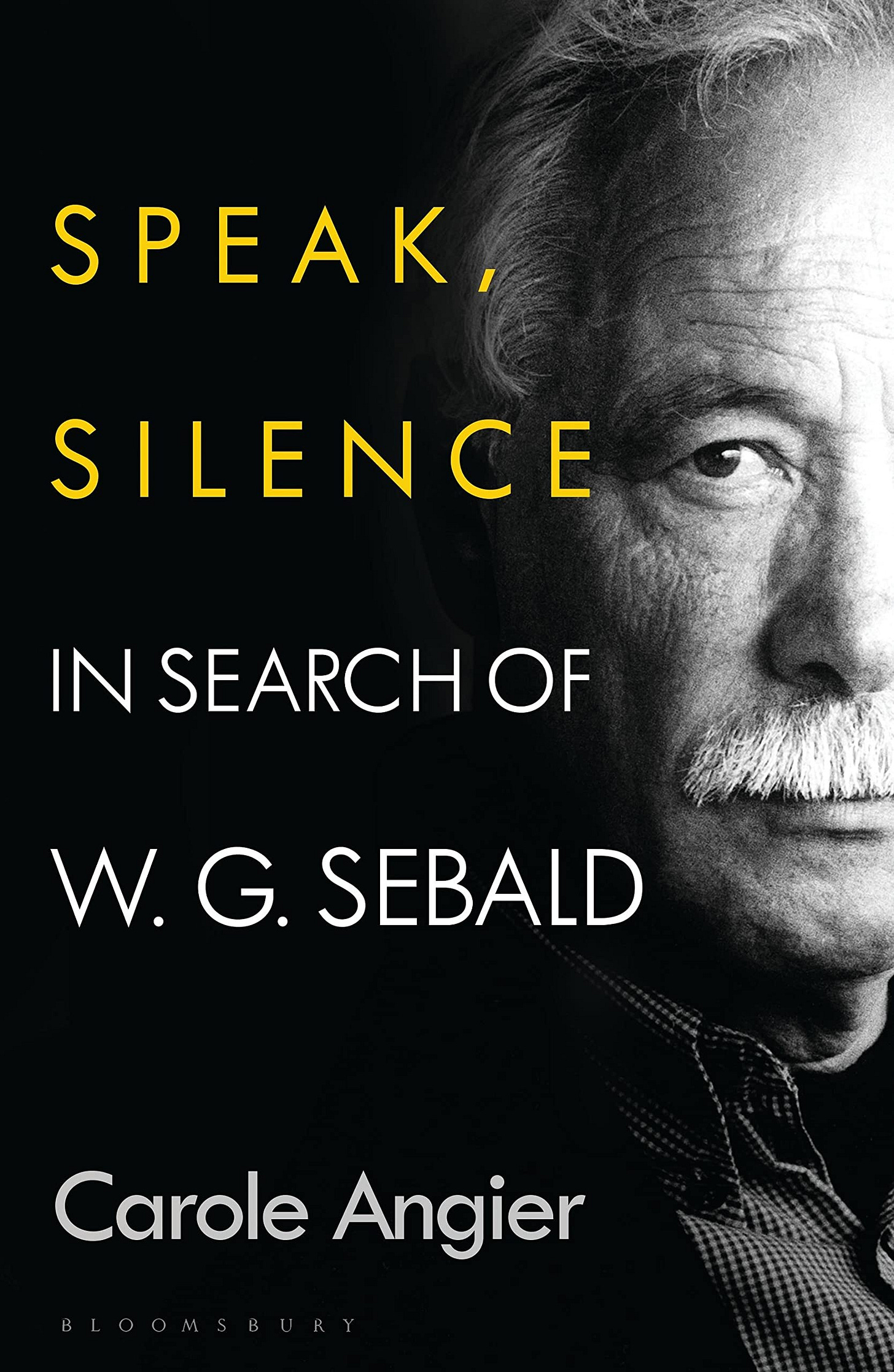

But another persistent distraction is the notion—now practically a received idea—that Sebald’s books cannot be classified as either fiction or non-fiction, or that they occupy a space between that all-too-familiar dichotomy. This is nonsensical; the difference between fiction and non-fiction is defined by both convention (what is to be labeled fiction or non-fiction) and commitment (what the author claims to have intended to write). Referentiality alone (whereby we are led to assume that non-fiction refers, cleanly and confidently, to ‘the real world’ or to ‘facts’) cannot decide the issue, because a novel can just as easily refer to the real to suit its purposes, or even signify reality, as Barthes observed.10 Sebald committed to fiction, the single most important piece of evidence for this being that he did not commit to ‘non-fiction’ and all its attendant rhetoric of facticity. And Sebald was hardly the first author charged with blurring the boundary between fact and fiction, though in his case for us to insist on that blurriness instead of recognizing fiction when we see it would foreclose further analysis. It is as novels that Sebald’s books Vertigo (1999), The Emigrants (1996), The Rings of Saturn (1998), and Austerlitz (2001) will have any lasting merit and interest. In his review of Angier’s biography Ryan Ruby remarks that her “defence” of Sebald’s misrepresentations is “the correct one,” namely “novelistic prerogative.” But ultimately—or more accurately, at present—it is through a subtle tension between fictionality and real subject-matters that Sebald’s novels enact their formal experimentation, and thereby have significance, and perhaps even utility.

Before we examine the typical form of the Sebaldian novel, we should establish some idea of what exactly ‘the Sebaldian’ is, or at least what it is understood to be. As Ruby explains:

Sebald’s writing is known for four things: its thematic preoccupation with the aftereffects of the Holocaust and the Second World War; the interspersion of photographs, documents and reproductions of paintings and other visual media throughout the texts; the floridity, antiquarianism and melancholy tone of its prose; and, finally, its so-called ‘metaphysics of coincidence,’ the way an apparently associative series of random details and incidents […] [reveals] itself, in the end, as having operated according to a complex, lattice-like order from the beginning. (134)

This is representative of what is generally thought to be characteristic of Sebald’s work, but it should be amended. The First World War is no less significant in Sebald’s work than its successor, and the Holocaust is not always directly referenced; sometimes the presence of history in a Sebald novel is to be inferred (or not) by the reader, depending on what knowledge of history they already have. We will find that this element of contingency in the reading experience is actually modelled by Sebald’s novels. His use of visual media could easily overtake any discussion of the novels, but here it will suffice to say that in Sebald the photograph becomes emblematic of apparent non-fictionality—which is to say, reliable or authoritative referentiality—that ultimately cannot be trusted. Finally, Ruby overstates the importance of what he identifies as a “so-called ‘metaphysics of coincidence.’” Critics and readers have indeed been tempted or trained to find what Ruby describes in Sebald, but nothing requires that we assemble the narratives, fragments, and details that make up a Sebaldian novel into anything resembling a metaphysics. We may find another description of Sebald’s work that Ruby provides more useful: “As with the great modernist novelists, of whom he is perhaps the last, [Sebald’s] is primarily a synthesizer’s achievement” (135). I contend, to the contrary, that Sebald is not one of the last modernists, but a particularly belated modernist. This implies an aesthetic standpoint both attuned to the fundamental belatedness of textual transmission and formed by an immediately historical sense of belatedness. Sebald grew up in the German aftermath of WWII and the Holocaust, and his growing frustration or disgust with the “conspiracy of silence” in Germany clearly motivated his scholarly and fictional work. His formal experimentation makes him comparable to canonical modernists, but in Sebald’s case both form and content—and as we will see, the content of form—are modulated through a sensibility and an idiolect that should be understood as both fundamentally and historically belated.

III. Fiction after the fact

To clarify the notion of ‘the Sebaldian’ that I have been less directly considering so far, I want to turn to the first section of Sebald’s first novel, Vertigo, titled “Beyle, or Love is a Madness Most Discreet.” We can think of this chapter as an introduction to Sebald’s literary form and style. It begins with a sentence that could pass all too easily for non-fiction: “In mid-May of the year 1800 Napoleon and a force of 36,000 men crossed the Great St. Bernard pass, an undertaking that had been regarded until that time as next to impossible” (3). A little later, Sebald’s narrator writes: “Among those who took part […] and who were not lost in nameless oblivion, was one Marie Henri Beyle” (4). Note the brief, quietly editorial comment on the “oblivion” typically repressed, as it were, by historical narration: to not have been forgotten is noted as a privilege. There follows something like a biographical sketch of the writer more commonly known as Stendhal, though he is never referred to by that name here. So in this first section of Vertigo the narrator initiates what will become a familiar Sebaldian device in its own right: the reporting of the novel’s thematic preoccupations as if they were discovered in the writings or artefacts of a historical personage. In this case we are informed: “The notes in which the 53-year-old Beyle, writing during a sojourn at Civitavecchia, attempted to relive the tribulations of those days [in military service] afford eloquent proof of the various difficulties entailed in the act of recollection” (5). In particular, the narrator explains that Beyle describes unreliable, because factually false, images in his memory, and “furthermore [he] writes that even when the images supplied by memory are true to life one can place little confidence in them” (7). We are told that Beyle was disappointed to recognize his own memories as having, in fact, originated from an engraving of a certain scene; Beyle warns of how external, ostensibly referential images “will displace our memories completely, indeed one might say destroy them” (8). These notions are not pursued in some argument, but rather allowed to arise, as if of their own accord, from the brief biographical account that the narrator has decided to set down for no apparent reason as of yet. But so far this chapter could, as I have said, pass for a rather ‘literary’ bit of biography; an essay, in other words, but not obviously a novel.

Fictionality enters the first chapter of Vertigo by way of contamination—or so one might conclude if one has taken the biographical essay this chapter appears to be at face value. That details from a story by Kafka should appear in the ‘life’ of Stendhal will be less surprising to those who read Vertigo expecting fiction—that is to say, who read Sebald without becoming distracted by vague ideas about the impossibility of categorizing his writing. Toward the end of the chapter the narrator describes how Beyle and one “Mme Gherardi” arrive at the small Italian port of Riva:

[…] where two boys were already sitting on the harbour wall playing dice. Beyle drew Mme Gherardi’s attention to an old boat, its mainmast fractured two-thirds of the way up, its buff-coloured sails hanging in folds. It appeared to have been made fast only a short time ago, and two men in dark silver-buttoned tunics were at that moment carrying a bier ashore on which, under a large, frayed, flower-patterned silk cloth, lay what was evidently a human form. The scene affected Mme Gherardi so adversely that she insisted on quitting Riva without delay. (24-5)

These two ‘real’ people, now characters in Sebald’s novel, encounter a scene from Kafka’s story “The Hunter Gracchus.” The two boys playing dice, the old boat, the silver buttons on the men’s tunics, and the flower-pattern of the cloth: these details make the interpolated allusion unmistakeable. But it can only be recognized as an allusion by those familiar with Kafka’s story; otherwise it will be understood by the diachronic reader to be a real scene first reported by Stendhal and then by Sebald, or by Sebald’s narrator. As Vertigo progresses through its four chapters (one of which similarly describes a certain period in Kafka’s life) the allusion recurs and becomes easier to spot. The third chapter, “Dr K. Takes the Waters at Riva,” suggests that the story was inspired by a ship Kafka saw at Riva; in the final chapter it becomes evident that the narrator has been fixated on that particular story since childhood. We finally learn that a hunter, killed by a fall in the mountains (like Kafka’s Gracchus), was brought back to the narrator’s village, where he glimpsed death perhaps for the first time, and that “a sailing ship was tattooed on the left upper arm of the dead man” (249). This experience occupied his mind and was made even more memorable by the severe illness the narrator survived shortly thereafter. So, when viewed synchronically (that is, in recollection, voluntary or involuntary) Vertigo has clearly been constructed precisely in order to make the origin of the Kafka story’s personal resonance for the narrator one of the novel’s final revelations. But no such revelation is provided for the problems of form raised by what might have been taken for non-fiction in this book. It is easy enough to recognize that all of Vertigo is effectively fiction, but this only indicates the real problems that the novel raises.

This effect of apparent or seeming non-fictionality being contaminated by fictionality, so to speak, is constitutive of Sebald’s writing. We can see now that to recognize Sebald’s books as works of fiction is to complicate the question of whether or not they ‘accurately’ reflect reality, and to begin to understand what they really accomplish. Their first accomplishment is to produce (in Vertigo and The Emigrants in particular) for the reader a realization: what appears non-fictional in these books has been rendered fictional by virtue of the form of these texts.11 This is to say that the narrator’s prose accounts of history and biography become mingled with outright fictions, but also that in a Sebaldian novel the reader is invited to recognize historiography and narrativization—especially insofar as the two are identical—as not so cleanly distinct from fictionality as one might want to assume. As Hayden White explains in The Content of the Form (1987): “Narrative becomes a problem only when we wish to give to real events the form of story. It is because real events do not offer themselves as stories that their narrativization is so difficult” (4). He goes on to ask: “What wish is enacted, what desire is gratified, by the fantasy that real events are properly represented where they can be shown to display the formal coherency of a story?” (4). This leads him to argue that “the very distinction between real and imaginary events […] presupposes a notion of reality in which ‘the true’ is identified with ‘the real’ only insofar as it can be shown to possess the character of narrativity” (6). Here our all-too-familiar distinction between fiction and non-fiction becomes less cleanly distinct. Our “wish” or “desire” for form all too often leads us to accept a “fantasy” as the standard of what is apparently least fantastical: history. If we recall just how painful and unsettling history can be, it will be easy to appreciate how non-trivial that desire is. But the form with which we have typically answered that desire—narrative discourse—has its own implicit content which it imposes onto the past with profound consequences:

If every fully realized story, however we define that familiar but conceptually elusive entity, is a kind of allegory, points to a moral, or endows events, whether real or imaginary, with a significance that they do not possess as a mere sequence, then it seems possible to conclude that every historical narrative has as its latent or manifest purpose the desire to moralize the events of which it treats. (14)

The desire for history to have an unambiguous significance is familiar, and intelligible: none of us would like to shrug at the complexities of the past and give up on ever making sense of it. Whether we would be right to see that as the only alternative is another question. As White claims, the historical narrative is a distinct and peculiar way of writing the past, its current predominance notwithstanding:

Unlike that of the annals, the reality represented in the historical narrative […] displays to us a formal coherency to which we ourselves aspire. The historical narrative, as against the chronicle, reveals to us a world that is putatively ‘finished,’ done with, over, and yet not dissolved, not falling apart. In this world, reality wears the mask of a meaning, the completeness and fullness of which we can only imagine, never experience. (21)

As we have begun to see, Sebald has hardly returned to either the annals or the chronicle as forms for recording history; he prefers instead to embed more or less historical fragments within narratives we may take to be historiographical but that reveal themselves under pressure, or upon concluding, to have been constitutively fictional all along. But it is precisely because the historical narrative ends, and ends with meaning, that it implicitly moralizes, for “we cannot say […] that any sequence of real events actually comes to an end, that reality itself disappears” (23). No one in a literary classroom would try to interpret the meaning of a narrative text without considering its ending. White rightly insists that for a historical narrative to end has meaning as well. We should recall here Bergson’s distinction between la durée and l’entendu, the lived flow of time (to call it a series of discrete events would be to mispresent duration as Bergson sees it) versus our organization of time into moments, periods, or epochs. Historical narrative is to the past what a clock is to the subjective flow of time; we might consider here the moralizing (and indeed demoralizing) utilitarianism or instrumental rationality implicit in clock-time as organized time: ‘time is money’ and so on. White concludes by asking: “Could we ever narrativize without moralizing?” (25). Perhaps we could start by considering how narrative, conscious of what White has identified to be its moralizing content, could deliberately turn the content of the form toward a critical goal. Can we write morally without merely moralizing?

Those who know The Magic Mountain will recognize that it is by no means a ‘Sebaldian’ novel, but its formal peculiarity will be useful for thinking about what, exactly, a Sebald novel does and how it does it. With White’s argument about historical narrative in mind we should consider the novel’s foreword and how it pre-defines the novel to come:

[…] stories, as histories, must be past, and the further past, one might say, the better for them as stories and for the storyteller, that conjurer who murmurs in past tenses. But the problem with our story, as also with many people nowadays and, indeed, not the least with those who tell stories, is this: it is much older than its years, […] it does not actually owe its pastness to time […] the extraordinary pastness of our story results from its having taken place before a certain turning point, on the far side of a rift that has cut deeply through our lives and consciousness […] in the old days of the world before the Great War, with whose beginning so many things began whose beginnings, it seems, have not yet ceased. (xi-xii)

Here at the beginning of a very long novel, and thus one that implicitly demands we pay exorbitant attention to narrative production, Mann undermines the moral certainty otherwise implicit in narrativity as such. The narrator acknowledges that “pastness” is amenable to narration, indeed makes it tractable for ‘conjuring.’ The threat of misrepresentation, or of representation’s impossibility, looms. The event that can only be called an event after it has ended, and which is to make this story so much “older than its years,” is the so-called Great War. The past, then, is not all equally available to narrativity: some ‘events’ change the meaning of what came before, and thus that of life afterward: they generate a historically peculiar sense of afterwardness or belatedness, as the case may be. This is why Adorno insisted on asking whether one could live after Auschwitz, in which case morality itself became newly problematic (Negative Dialectics 363). And the Great War was an ending with a moral meaning or a meaning for morality as well—or so Mann’s narrator claims. As Jameson observes:

[…] this is an illusion specifically projected by the structure of the Zauberberg itself which is designed, in advance, to appear belated, and a message in a bottle or a recapitulation of a vanished past. But this is so […] because the very reading mode itself of which it is the monument is itself in eclipse, something then proleptically signaled in advance (in a kind of fictive premonition) in the form of the media and specifically of film and phonograph. (65)

This, then, is what Jameson identifies as Mann’s peculiar method of form production: to make the reading of The Magic Mountain a “monument” to what the novel is already reconstructing as it laments its “pastness.” That the novel ends in a scene of war—where the protagonist Hans Castorp “disappears from sight” for the narrator, because there are no protagonists in war—does moralize, but not necessarily in a way that we need to distrust (706). Reading Mann’s novel is a way of coming to understand a historically precise experience of afterwardness, as Jameson explains:

[…] now, after so many pages, ‘art’ is also the memory of the extended reading experience that finally designates itself in conclusion, in the reflexivity both characteristic of modernist form production in general […] and also of this unique monument to aestheticism, as ambiguous as the very ambiguities in which it so triumphantly revels. (93-4)

We could say that what Jameson identifies as “form production” is also—or is intimately related to—the more familiar idea that certain texts, especially experimental ones, ‘teach’ their readers how to read them. In other words, form production is potentially reader production as well, which means that an experiment in literary form can actually model or demonstrate to readers certain ways of making sense or assembling meaning. Sebald combines with that meaning-making demonstration the implication that any project of historical narration (fictional or factual) is fundamentally ambiguous, but worth attempting all the same. We should also note the implication made by Mann’s narrator in the preface to The Magic Mountain: what began with the War is, circa 1924, not finished beginning. The present is where (or more precisely, when) the past and the future are to be won or lost.

IV. Sebald and his precursors

Having introduced Mann as one German antecedent for Sebald, I want to describe a notion of intertextuality not defined by what one critic called ‘the anxiety of influence.’ For it is not simply as influences or antecedents but also as precursors that modernists like Proust, Mann, Jorge Luis Borges, T. S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf are relevant to an account of Sebaldian form.12 We can be confident that some or all of them did actually influence Sebald, but I am not interested in Sebald’s influences as such.13 Instead I intend to draw Sebald ‘into conversation’ (as we say) with Eliot, Borges, and Woolf in order to indicate by way of comparison what the content of Sebaldian form may be. At the same time this will be an experiment in more openly practicing the sort of intertextual linkage—the so-called “metaphysics of coincidence”—that produced Sebald’s novels in the first place. Just as the Sebaldian novel encourages a certain readerly attention and scepticism, so can criticism embody and encourage a centrifugal curiosity (hopefully without sacrificing all coherence). The experience of being led astray—be it in reading a novel or a critical essay—has merits that we are yet to fully appreciate.

The broad and persistent influence of Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919) is itself an influential presupposition for modernist studies; nevertheless that essay remains an important example not only of modernist literary criticism, but also of form production. Eliot sets out to define his own poetic and critical practice, and to defend the kind of work he is trying to create, namely a poem like The Waste Land (1922).14 At the same time Eliot’s essay is a work of criticism, not a poem or novel, and given that it lays out an “Impersonal theory of poetry” (104) we should primarily consider its claims as those of a critic. However, I first want to note that Eliot’s emphasis on the importance of criticism throughout this text anticipates what Adorno will argue in his infamous essay “Cultural Criticism and Society” (1951).15 He claims:

Culture is true only when implicitly critical, and the mind that forgets this revenges itself in the critics it breeds. Criticism is an indispensable element of culture that is itself contradictory: in all its untruth still as true as culture is untrue. Criticism is unjust not when it dissects—this can be its greatest virtue—but rather when it parries by not parrying. (149)

In other words, culture should be critical, and criticism—within culture as such, or within a critical discourse—cannot afford to shirk its real responsibilities, which are ultimately to truth. The phrase “in all its untruth still as true as culture is untrue” can be understood to claim that criticism’s purpose is to reflect truth back to untruthful culture, even by exaggerating or, we may say, fictionalizing. I point to this continuity, such as it is, between Eliot and Adorno because their differences (in terms of ideology and biography) are more obvious than their similarities, but to connect them may still be productive.

What primarily interests me in Eliot’s criticism is his particular notion of what tradition is, and how the present writer should relate to it. Eliot writes of a “great labour” to be undertaken by the would-be poet, which “involves, in the first place, the historical sense,” and that sense “involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence” (100). Eliot is careful to stress that he is not simply advocating raw erudition, or for the poet to have an impressive and imposing knowledge of literary history:

This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional. And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his contemporaneity. (100-1)

This amounts to the claim that understanding the present is inextricable from understanding the past, from “historical sense.” And at the end of the essay Eliot brings futurity into his theory as well: “[The poet] is not likely to know what is to be done unless he lives in what is not merely the present, but the present moment of the past, unless he is conscious not [only] of what is dead, but of what is already living” (108). Historical sense is not antiquarianism: it is something like an ethical understanding of time, where the present moment is affirmed in its reality but only insofar as that reality includes what came before and what may follow. What remains to be seen is how exactly one can read toward that understanding.

In order to see how Sebald’s writing—oriented as it is toward both memory and reading—innovates the modernist form production practiced or described by Proust, Mann, Eliot, and others, we can turn to Borges and his essay “Kafka and His Precursors” (1951). Borges explains that “after spending a little time with [Kafka]” he thought that he could “recognize his voice, or his habits, in the texts of various literatures and various ages” (363). He provides a few examples which present a similarity of form, or of tone, and concludes:

Kafka’s idiosyncrasy is present in each of these writings, to a greater or lesser degree, but if Kafka had not written, we would not perceive it; that is to say, it would not exist. […] The fact is that each writer creates his precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future. (365)

Here Borges actually cites “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” and he has clearly been inspired by Eliot’s formula: “the past [is] altered by the present as much as the present is diverted by the past” (101). Thanks to White’s argument about historical narrative we can see the implications of this line of thinking for the possibility of understanding history: we can only understand the present and the past together, and a false division between the two (whereby we assume that histories have endings) will only lead to confusion. But Borges is also reorienting Eliot’s critical paradigm, for the recognition of precursors is a task not exclusively reserved for the critic or poet trying to place himself within tradition—it is something any and every reader can do.16 This is not about anxiety provoked by influence; we are now concerned with the less ambitious projects of connection-building that begin accidentally in the process of reading.

Here we should recall again the Bergsonian and Proustian idea of involuntary recollection (pun intended). Following Bergson, Proust emphasises the role of raw, immediate sensuality in the recovery of ‘lost time,’ and in Swann’s Way it is the highly particular taste of the madeleine dipped in the tea that triggers an involuntary recollection. But we are all familiar with a kind of involuntary memory peculiar to the act of reading, where a word or phrase spontaneously reminds us of another word or phrase, or an experience, be it mediate or immediate. And this particular kind of involuntary recollection is possible thanks to the written word, or to media generally, for this is really a feature of all cultural experience; these recognitions of connection are the basis for Borges’ ‘precursors.’ Each writer makes new recognitions possible for their readers. Even if one doesn’t have the specific goal of collecting precursors for a certain author, what we can think of as experiences of involuntary intertextuality really must form the basis for careful reading, analysis, criticism, and theoretical writing. But before long we will find that there is a fair amount of work entailed by this. As Jameson remarks:

The coherence of any serious and extended engagement with cultural experience depends on a productive coordination between contingency and theory; between chance encounters and an intellectual project. It is true that we always try to resolve this tension one way or the other, by philosophically confirming the aleatory nature of the experience, or subsuming the personal under a theoretical meaning. But the vitality of the engagement depends on keeping the tension alive. (ix)

The same is true of this project, and to admit that is not to borrow Jameson’s critical prestige. All readers, even if they do not think of themselves as theoretical, or as having a project, find that whatever their “cultural experience” amounts to will arise from both agency—the selection of reading material, along with whatever reading method one might adopt—and contingency.17 We have to admit that the pattern-forming, analytical, critical, and even dialectical work of reading depends upon “chance encounters” analogous to, or simply identical with involuntary memory. We may even say that if perception and memory are inextricable, every recognition is also somehow a recollection. These recollections are most productive when they develop into the secondary recognition of difference, of what is not actually identical after all. So we can see, now, that in Sebald’s novels what some have called a “metaphysics of coincidence” is actually a more sophisticated dynamic: one where apparent contingency, the coincidences orchestrated by the author, refract or refigure the actual contingency that enters into form production as much as into reading itself.18 What patterns the reader may observe in The Rings of Saturn are not finally meaningful because of their content. The first meaning or content of a pattern is its form: it connects what was otherwise disparate and fragmented. For example, in Rings the narrator’s recurrent fixation on traces of cremation and fiery destruction has no submerged or subtextual meaning in terms of content; rather, each instance of destruction or loss has a peculiar pathos to offer on its own. But through the form of a pattern that one reader (the narrator) is attempting to identify and record, recurrence itself defamiliarizes our own desire for spontaneous recognitions, and for the unexpected perception of meaning (or its shape) amongst fragments and traces of catastrophe. As Adorno suggests in Minima Moralia, “truth itself depends on the tempo, the patience and perseverance of lingering with the particular […] what proceeds to judge without having first been guilty of the injustice of contemplation, loses itself at last in emptiness” (77).19 Time wasted is the prerequisite for time used—and following our recognition of this the distinction between useful and frivolous uses of time, between work and play, should collapse.20 To the extent that play and work correspond to fiction and non-fiction we can also say that if we intend to be “guilty of the injustice of contemplation” we will have to subordinate, if not abolish both distinctions to begin with.

But as Jameson recognizes, involuntary recollection or “lingering” alone will not achieve very much in practice. Research and non-spontaneous thinking are necessary to develop a surprising remembrance or connection into something with critical, ethical, and potentially political significance. Most of those recollections are not even fully intelligible—let alone communicable—without some development through analysis or contextualization. One might even want to posit a crucial dialectic between involuntary intertextuality and the research practices that will always threaten to discredit, devalue, or otherwise diminish those cherished patterns and connections. So we have to move slightly past Bergson and Proust and acknowledge that we cannot trust memory alone to accomplish very much. In The Waste Land this kind of textual or readerly memory informs both content and form (and, to be sure, the content or meaning of the form), and the whole poem is a non-literal, non-realist representation of Eliot’s present via fragments of the past:

“Do

“You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

“Nothing?”

I remember

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

“Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?” (II. 121-26)

Even Shakespeare, chief emblem of the English literary tradition, here lives only as the “fragments I have shored against my ruins,” (V. 430) as though spontaneous and involuntary remembrance of text has become useless and aggravating—and is nevertheless clung to, as one last source of meaning, by the voices or consciousnesses that inhabit Eliot’s waste land. The alternative would seem to be nothingness, an empty head, though as the scene above shows, in interpersonal relations absolute idiosyncrasy and inwardness—asociality—tends to amount to nothingness. At any rate, one need only recognize (or research) the line from The Tempest in the passage above, and notice its recurrence throughout Eliot’s poem, to begin to see what is supposedly so hard to understand about The Waste Land: making sense out of nonsense or from fragments of sense is difficult, it guarantees nothing, and it is nevertheless all we can do when we are confronted by despair, fragmentation, social degradation, atrocity, personal illness, or simple unhappiness. Thus Eliot’s poem, far from being deliberately or maliciously difficult, actually makes our atomized, fragmented, socially and materially and spiritually deprived condition a little easier to see, and thus easier to think about, and thus easier to resist. What is obvious about The Waste Land is its strange and apparently incoherent surface, and today that may be its most persistently relevant meaning. As Adorno claims in “Cultural Criticism and Society,” the successful work of art “is not one that resolves objective contradictions in a spurious harmony but one that expresses the idea of harmony negatively by embodying the contradictions, pure and uncompromised, in its innermost structure” (160). The Waste Land may not be easy to read, but its difficulty is slight compared to the objective disharmony it attempts to resist through a form devoted to fragments.

In The Rings of Saturn that objective problem is no less subjectively melancholy, and yet not exactly one of absolute pessimism. Indeed, it might be the orientation of this novel to alterity and diversity—that is, to the other in general, to various particular histories of suffering and violence, and to the destruction of the natural world—that saves it from collapsing. Far from being merely melancholy, The Rings of Saturn indicates that the spontaneous involuntary recollections or recognitions of any reader are always imbricated with urgent ethical problems. What we choose to attempt to understand is actually an ethical question, especially because today attention is increasingly attenuated and diverted, with clear political consequences. As Adorno writes in the lecture on “Working through the Past”: “We are not simply spectators of world history, free to frolic more or less at will within its grand chambers, nor does world history, whose rhythm increasingly approaches that of the catastrophe, appear to allow its subjects the time in which everything would improve on its own” (14). The problem with readerly (or ‘bookish’) curiosity as a motivating factor for an ethical relation to the past, to alterity, and to both insofar as they make up the future, is that reading tends to primarily motivate more reading, not action. Therefore reading, literature, and aesthetic form generally have to be turned against themselves: forms have to be produced, and criticism written, that challenge the individual reader not to take for granted either culture or the safety necessary for its contemplation. When that bare minimum is not met culture becomes exactly as untrue as Adorno feared.

It is fitting, then, that the form of The Rings of Saturn is in part produced as though the novel were a failed travelogue: the record of an intended vacation that has become, in the moment and through its narrativization (if we can speak of a narrative in Rings), instead something rather more gloomy; or in Adornian terms, as negative as the present moment requires. Rings begins as follows:

In August 1992, when the dog days were drawing to an end, I set off to walk the county of Suffolk, in the hope of dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work. And in fact my hope was realized, up to a point; for I have seldom felt so carefree as I did then […] At all events, in retrospect I became preoccupied not only with the unaccustomed sense of freedom but also with the paralysing horror that had come over me at various times when confronted with the traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident even in that remote place. Perhaps it was because of this that, a year to the day after I began my tour, I was taken into hospital in Norwich in a state of almost total immobility. (3)

If we assume that the narrator is a version of Sebald (though the recognition of similarities between narrator and author should lead us to realize that the narrator is a non-binding fictional expression of the author), then we can also assume that the “long stint of work” that has made the narrator feel so empty was either teaching, or research, or creative writing, or some combination of these. The walking tour or pilgrimage that the narrator undertakes does secure for him some measure of ‘freedom’ and, we may infer, happiness. But we should ask what it means that he could not help recognizing and being horrified by “traces of destruction” in Suffolk and what relation this may have to his subsequent illness. It may be that his work as a reader, broadly speaking, has predisposed him to involuntarily ‘remember’ histories of destruction whenever he comes across their traces. The narrator’s hospitalization indicates, then, that what we habitually ignore is the literally sickening and potentially overwhelming weight of the past.21 Writing becomes a place in which to understand such an overwhelming and even debilitating experience; by virtually re-enacting the walking tour the narrative, such as it is, could also be called a prosthesis that restores mobility. Those involuntary recognitions of horror throughout the pilgrimage are themselves the belated impetus for the narrator’s record of those recognitions and, in turn, their context as supplied by research: “It was then [in hospital] that I began in my thoughts to write these pages” (3-4). To specifically grasp the kind of “traces” that the narrator records, we can consider one of the chapter-synopses provided in the novel’s “Contents”:

III. Fishermen on the beach — The natural history of the herring — George Wyndham Le Strange — A great herd of swine — The reduplication of man — Orbis Tertius.

Real subjects have been placed next to Borges’ virtual world, “Orbis Tertius”—a fiction that was, in Borges’ tale, to eventually overtake reality. So much for the facticity of this historically-conscious travelogue. And these synopses do not appear as subtitles within the third chapter, so their purpose, and that of the whole “Contents” section, can seem obscure. It is as though the “Contents” are a post-scriptum outline of the book’s content, if reduced to content as such—a gesture made outside the supposedly ‘proper’ body of the text which nevertheless contextualizes our understanding of the text ‘proper’—not unlike Eliot’s notes to The Waste Land, which are themselves a peculiar little narrative, or fiction, of literary composition.22 So the content that the reader of Rings encounters, as in Vertigo and The Emigrants, is ostensible non-fiction that comes to be recognized as more or less fictional, and that will nevertheless address itself to real histories, problems, and horrors. And if the Sebaldian form is one of fictionalized nonfiction, what is the content of that form? I suggest it is the imperative to record, along the lines of what Adorno writes about remembrance, but also fictionality without narrativity, or at least without traditional narrativity insofar as it operates moralistically in the way White describes. What narratives appear or arise in one of Sebald’s novels are not only peculiar or idiosyncratic, but also defamiliarizing. We should be led by his books to reconsider our own desire to receive the past as a relatively neat story. Instead of applying narrative to the past, Sebald applies fiction—not by falsifying absolutely (though he does fictionalize), or by imposing what we can easily recognize as narrativity—but by insisting that fiction itself is a valid means of attempting to understand the past, the present, and the future. One saving feature of Sebald’s novels is that they model, and even encourage nonfictional research as much as intertextual fiction-perusal, because those are the activities that make up whatever narrative it may have; he does not imply that fiction should simply replace history. By foregrounding the unreliability of both memory and media, and by making fiction look like nonfiction, Sebald asks that we rethink the presupposed chasm between the two: that is, the rift between culture and ‘the real.’

If there is one overarching narrative in The Rings of Saturn, it is the narrative of the book’s composition, the production of its form—and that story involves illness, which we can no longer ignore. The question of illness and its relation to reading is not a supplement to the question of form in Sebald. It is really the question of the possibility and modality of reading (along with all that ‘reading’ has come to carry with it in this essay) not just as a mind, but as a frail subject. In thematic terms illness could be made to link all the modernists I have discussed so far, and we cannot help but think of the COVID-19 pandemic, nor should we completely bracket or abstract it from our thinking about the past. I do want to conclude with one last ill modernist, or one last modernist of illness: Woolf, “‘in bed with influenza’” (103). But Woolf’s essay “On Being Ill” is not just thematically relevant; she examines exactly the kind of reading experience that we have been considering so far. Woolf does rather overstate the absence of illness in literature, but nevertheless she makes an astute point: “literature does its best to maintain its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear […] On the contrary, the very opposite is true. All day, all night the body intervenes” (101). We like to think we have forgotten nothing, and we are especially given to assume that we have not forgotten the body—how could we? Woolf reminds us that it is far easier and more common to do so than we may prefer to assume. She goes on to describe how illness has a defamiliarizing effect not unlike that of literature:

‘I am in bed with influenza’—but what does that convey of the great experience; how the world has changed its shape; the tools of business grown remote;[…] friends have changed […] while the whole landscape of life lies remote and fair, like the shore seen from a ship far out at sea […] the experience cannot be imparted and, as is always the way with these dumb things, [one’s] own suffering serves but to wake memories in [one’s] friend’s minds of their influenzas, their aches and pains that went unwept last February, and now cry aloud, desperately, clamorously, for the divine relief of sympathy. (103)

Here we could pause to look back at Sebald’s narrator, in the first chapter of Rings, hospitalized and remembering his own reading of Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”:

I dragged myself, despite the pain, up to the window. […] I could not help thinking of [Kafka’s story] […] And just as Gregor’s dimmed eyes failed to recognize the quiet street where he and his family had lived for years, so I too found the familiar city […] an utterly alien place. (5)

Unless we are confident that defamiliarization—the suspension not only of familiarity, but also of what we habitually take to be ‘normal’ and ‘healthy’—is useless, we cannot discount these apparently minor experiences. Precisely because narrativity is preeminent to the point of becoming habitual in historiography (practiced professionally or otherwise), and because narrativity tends to impose moral meaning, we still have use for opportunities to reconsider what we desire of the past. We may find unhealthiness, as related to actual illness but not predefined in terms of medical pathology or diagnosis, a useful concept whenever we need to rethink the normal, healthy status quo.23 We could say that while the traumatic experience unexpectedly ‘returns’ and throws the present into a crisis originating in the past, illness creates a present crisis that will prove either chronic or period-bound. Thus illness, as a figure of distinct and intelligible disruption in normality and health, can be thought of as a figure for our experiences of discontinuity. Where trauma forces one to confront the past and thus violently insists on continuity between past and present, ‘ordinary’ illness confronts one with the discontinuity between the healthy past and the unwell present. As Hayden White has suggested, “we require a history that will educate us to discontinuity more than ever before; for discontinuity, disruption, and chaos is our lot” (“The Burden of the Past,” 134). Sometimes the meaning and even the beauty of the fragment is that it is intractable for pattern-formation, that it resists our impulse to order, connect, and cohere. Sometimes the fragment reminds us of the experiences of disconnection, incoherence, and chaos that we commonly call illness—and by virtue of its presence alone suggests that some trace of what was damaged or broken long ago has nevertheless survived. Destruction scatters as much as it erases, but when one meaning has been violated or ripped apart the fragments may found another.

Woolf concludes her essay by recording, in truly Sebaldian form (which indicates that Sebald is more Woolfian than we might have expected), an experience of readerly sympathy: a chance encounter with an obscure detail in a work that might never have attracted Woolf’s attention when she was healthy. Famously, Woolf claims: “Rashness is one of the properties of illness […] and it is rashness that we need in reading Shakespeare” (108). But before long—after just one paragraph, in fact—she writes:

But enough of Shakespeare—let us turn to Augustus Hare. There are people who say that even illness does not warrant these transitions; that the author of The Story of Two Noble Lives is not the peer of Boswell […] So be it. The law is on the side of the normal. But for those who suffer a slight rise of temperature the names of Hare and Waterford and Canning ray out as beams of benignant lustre. (110)

Woolf posits illness as one way out of literature as it is typically defined by cultural canons: when we are ill we may read—and want to read—what we would normally discount.24 Here we should recall Adorno’s later repudiation of what passes for “normality” and “health” in everyday life, as elaborated in “Working through the Past,” Minima Moralia, and elsewhere. The suspension of assumptions that Woolf sees illness enacting is one that could be fruitful, if not simply necessary, for ‘healthy,’ logical, rigorous, researched, and professional work with the past and the words with which we try to understand it. Or, more simply, we could say that true thought can never be entirely healthy. And with Adorno’s “lingering with the particular” in mind we could suggest that today malingering with the particular will prove more useful than we have tended to assume.25

Woolf paraphrases a narrative from Hare’s book, the one she has discarded Shakespeare for, and her essay ends with a minor detail that may or may not be astonishingly moving as one reads it. It is, in short, a recorded trace of the anguish of loss: a written account of a mark on a curtain which Woolf transmits to her reader:

[…] never could Sir John Leslie forget, that when he ran downstairs on the day of the burial, the beauty of the great lady [Lady Waterford] standing to see the hearse depart, nor, when he came back, how the curtain, heavy, mid-Victorian, plush perhaps, was all crushed together where she had grasped it in her agony. (110)

To conclude not with Shakespeare—whom, according to Woolf, we may need to read with the ‘rashness’ of illness—but with a small detail found in a book apparently not worth reading, is for her essay to ultimately designate “the very reading mode itself of which it is the monument,” as Jameson writes of The Magic Mountain. Thus both Eliot and Woolf have demonstrated how sheer novelistic length is only one means for reflexively exploring the relation of reading to time and memory; fragmentary poetics and even the personal essay can achieve different results of similar significance. And Sebald, at the end of a chapter defined by illness, concludes with one of his typically essayistic and novelistic evocations of our desire for meaning:

[Thomas] Browne [in the essay “Urn-Burial”] scrutinizes that which escaped annihilation for any sign of the mysterious capacity for transmigration he has so often observed in caterpillars and moths. That purple piece of silk he refers to, then, in the urn of Patroclus—what does it mean? (26)

No answer will be given. We have to decide for ourselves what to make of the fragments shored against our ruins. The error would be in ignoring, out of a false sense of normal, healthy wholeness, what seems merely fragmentary or useless, be it an involuntary recollection, an obscure historical detail, an abandoned photograph, or even a scrap of fabric.26 More than memento mori, and more than rescued pieces of the past, those fragments are the materials of form-production and futurity.27 The answer to our desire for understanding is not simply the novel, or the poem, or the personal essay. Reading and writing themselves, prior to categorization, are among the best ways of attempting to understand time available to us. And just as we need to understand the past in order to understand the present, and perceive our present through our memories, so do we need to think of reading and writing as oriented not toward the past or the future, but toward the present as the place where past and future are real.28 Adorno proposes that “[no] other hope is left to the past than that, exposed defencelessly to disaster, it shall emerge from it as something different” (Minima Moralia 167). In turn I would suggest that in the face of imminent catastrophes no hope is left to the present other than that by rescuing the past, without misunderstanding or betraying it, we might begin to build a future.

As I see it this essay should end by designating itself as a beginning, and as such its implications are twofold. Just as a novelist like Sebald should be accorded the freedom, so to speak, to produce fiction that will not have its significance tested against either factual historiography or biography, so should the reader have the freedom to pursue involuntary recollections and chance encounters in the hope that those might lead to, for instance, a consequential ideology-critique or even to a truly utopian thought that breaks through linguistic and ideological barriers. Thus the idiosyncratic and the personal may found the political. But all this talk of freedom threatens to become disingenuous. As Terry Eagleton notes, “the vast majority of [people] throughout history have been deprived of the chance of living by [culture] at all, and those few who are fortunate enough to live by it now are able to do so because of the labour of those who do not” (187). If one has been granted the freedom to live by culture today—to make the study of culture one’s passion or work or both—one should recognize that such freedom is neither equitably granted nor guaranteed in the future. The concrete freedoms some of us enjoy now (the time, security, and resources required to study culture) should be put to work with genuine exigency—that is, political exigency, not one of the ingenious exigencies that literary scholarship is so fond of producing. Those fictitious urgencies that are supposed to justify so-called ‘knowledge-production’ are more perniciously misrepresentative than any fictionalized or unauthorized biography. The subjective experiences this essay has tried to revaluate, and that have been placed under the sign of the ‘involuntary,’ have no validity or human meaning outside of their voluntary use in the struggle for real freedom. Like ‘decolonization,’ freedom is not a metaphor, nor is form.29 We live in the forms, structures, and systems that organize social and material existence no less than in those that organize and produce culture, so we ought to remember that form production is not relevant to either culture or politics: it is relevant and significant only to the extent that we understand how culture and politics are inextricable. It is not too late to begin, but it is far too late not to.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor. “Marginalia on Mahler.” 1936. Telos 87, 1991, pp. 79-84. https://doi.org/10.3817/0391087079.

—. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. 1951. Translated by E. F. N. Jephcott, 1964. Verso, 2005.

—. Can One Live After Auschwitz? : A Philosophical Reader. Edited by Rolf Tiedemann, translated by Rodney Livingstone et al. Stanford UP, 2003.

—. “Cultural Criticism and Society.” 1951. Tiedemann, 2003, pp. 146-66.

—. “The Meaning of Working through the Past.” 1960. Tiedemann, 2003, pp. 3-18.

—. “Commitment.” 1962. Tiedemann, 2003, pp. 240-58.

—. Negative Dialectics. 1966. Translated by E. B. Ashton, 1973. Routledge, 2004.

Barthes, Roland. The Rustle of Language. Translated by Richard Howard, California UP, 1989.

Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. Translated by Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer. 1912. Dover Philosophical Classics, 2004.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 1968. Mariner Books, 2019.