Smells like Virginia Woolf

Notes on The Hours

One of the more persistent truisms about Virginia Woolf’s novels is that, for all of Woolf’s interest in the cinema as such, they are very difficult to adapt to film. But it is also difficult to adapt Woolf to fiction, and one shortcut is to do so directly, or metafictionally, as Michael Cunningham does in his novel The Hours (1998). The gambit of the novel is to borrow the one-day-in-the-life, or the-life-in-one-day, structure from Mrs. Dalloway and apply it to three fictional women: a version of Woolf herself (played in the film by Nicole Kidman and a plastic nose) as she begins to write her fourth novel in 1923; Laura Brown (Julianne Moore), an unhappy American ‘housewife’ living in suburban Los Angeles in 1951 and reading Woolf’s novel; and Clarissa Vaughan (Meryl Streep) in New York City, 2001, another reader of Woolf who also happens to resemble Mrs. Dalloway, which her friends never fail to point out. The novel opens with Woolf’s suicide, with the letter cited in full. This prologue is oddly moving, and ambiguous, ending as it does with the suggestion that Woolf is unusually perceptive, or receptive, even in death:

Here they are, on a day early in the Second World War: the boy and his mother on the bridge, the stick floating over the water’s surface, and Virginia’s body at the river’s bottom, as if she is dreaming of the surface, the stick, the boy and his mother, the sky and the rooks. An olive-drab truck rolls across the bridge, loaded with soldiers in uniform, who wave to the boy who has just thrown the stick. He waves back. He demands that his mother pick him up so he can see the soldiers better; so he will be more visible to them. All this enters the bridge, resounds through its wood and stone, and enters Virginia’s body. Her face, pressed sideways to the piling, absorbs it all: the truck and the soldiers, the mother and the child.

Perhaps the implication here is that Woolf’s mode or voice, her capacity to seemingly “absorb it all,” will live on after her death; this would seem to be the overarching implication of the whole novel, which is simultaneously about the actual influence of Mrs. Dalloway on the characters, and the uncanny sense that there are Mrs. Dalloways everywhere for those who care to see them. This last notion is, I think, the novel’s attempt to re-appreciate or re-emphasize one aspect of Woolf’s work: the significance of the quotidian, as memorably attested to by Erich Auerbach in his reading of To the Lighthouse. But Cunningham misunderstands this, and assumes that because Woolf adumbrates Mrs. Dalloway’s life through the events of one day, the novel is somehow about the “essence” of Clarissa Dalloway. Woolf’s novel is better understood as depicting how different one day is for many different people, and how the present of a single day is mediated by the past.

Another thing that Woolf’s novel is “about” is war and its impact on consciousness, so it is curious that Cunningham’s novel alludes to WWII but never really interrogates this theme or problem. In fact, Septimus sort of disappears in Cunningham’s rewritings of Woolf; only the poet Richard’s fate clearly alludes to the original character. To be sure, there is some of Woolf in Septimus, but by erasing Septimus’s war trauma Cunningham’s novel also erases its relationship with history. The film directed by Stephen Daldry goes even further in this direction, and this is its greatest flaw. It wants to use editing, music, and performance to establish sympathetic or thematic links between three narratives, using Woolf’s novel as a point of connection, but Cunningham and Daldry have little interest in Woolf’s real world: the historical upheavals she lived through and responded to through writing. For example, Laura Brown’s husband, Dan, is a veteran of WWII, but there is no indication that he himself has some concealed anguish or turmoil he cannot share with his wife, just as she hides her tears from him at the end of her day. One has the sense, throughout the film, that the men are “flat” characters, or even stereotypes, as in the case of Richard, the AIDS patient and oracular schizophrenic. While Woolf’s novel remains an indelible exploration of “shell shock,” The Hours has nothing to say about AIDS, and borrows topicality from it rather cheaply.

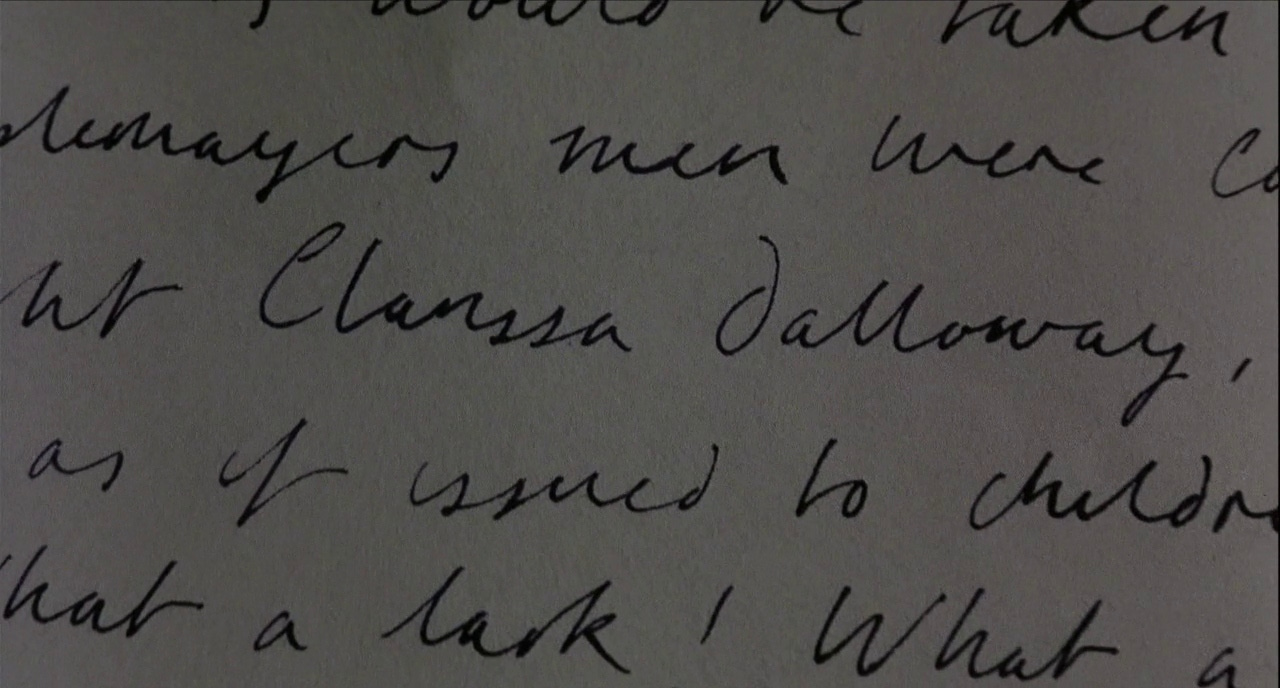

As in the novel, Daldry’s film begins with Woolf’s suicide, only without Cunningham’s attribution to Woolf of great perceptivity; also omitted is any real sense of Woolf as a writer. Even the suicide letter is abridged in the film; one notable elision is: “You see I cant [sic] even write this properly” (Cunningham 6). This is the one sentence from that letter that I have found most haunting, and it is blithely omitted from the film because the film is preoccupied with depicting Woolf as a figure of supreme artistic confidence. Both Cunningham and Daldry omit from their version of Woolf’s day any reference to the actual composition of the novel, which did not begin when Woolf sat down one morning and said to herself “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” The earlier short story “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street” is an early version of the opening pages of the novel, and Mrs. Dalloway was also a character in Woolf’s first novel. In the film this actual process of Woolf’s work as a writer is omitted (we also see nothing of her work as a publisher or craftsperson). This is curious, given that the film is also basically ashamed of writing even as it tries to affirm it. When Clarissa Vaughan goes to buy flowers for her party, on the occasion of her former lover Richard winning a literary prize, the florist tells her that she “tried” to read Richard’s novel. Clarissa apologetically replies that “it’s not easy.” But they may as well be speaking about Woolf’s novel, and the film is most offensive or embarrassing when it attempts to operate as a kind of replacement for prose. You might say the film has no nose for good prose (ha-ha).

One of the accidents of the cross-cutting or parallel editing in the film is that it actually emphasizes the radical differences of the three women, even as it attempts to insist on connections between them. They are, of course, all writing, reading, or re-enacting Mrs. Dalloway, but they have almost nothing else in common, except that they are all women, which arguably flattens them out even more. But the fascinating and ambivalent gesture of Woolf’s novel is to formally connect Clarissa Dalloway to Septimus Smith, without, I think, fully clarifying the content of that connection, or its meaning:

A young man had killed himself. And they talked of it at her party—the Bradshaws talked of death. He had killed himself—but how? Always her body went through it, when she was told, first, suddenly, of an accident; her dress flamed, her body burnt.

Whether Clarissa Dalloway is truly empathizing here, and what good that would be to anyone, is beside the point. Her reflections quickly turn metaphysical, and at the very least, by that token, Septimus makes a claim on her that pierces her habitus and seems to signify something fundamental:

A thing there was that mattered; a thing, wreathed about with chatter, defaced, obscured in her own life, let drop every day in corruption, lies, chatter. This he had preserved. Death was defiance. Death was an attempt to communicate, people feeling the impossibility of reaching the centre which, mystically, evaded them; closeness drew apart; rapture faded; one was alone. There was an embrace in death.

Then soon after: “Somehow it was her disaster—her disgrace.” And: “Odd, incredible; she had never been so happy.” The dead speak; or as Eliot wrote later:

And what the dead had no speech for, when living,

They can tell you, being dead: the communication

Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.

If wrong life cannot be lived rightly, then on a certain day to die might be a determinate negation of ordinary life’s negativity—or something like that. Ultimately the point of Woolf’s novel is that a sociality as fraught and problematic as that of interwar London brings about obscure intimacies and solidarities that are not fully apprehendable by the individual as such—but they are nevertheless felt. Lacking this shared historical ground, the women of The Hours do not, in the end, have any real connection except those contrived by narrative and by the stereotype as such. There are many women in Woolf’s novel, but they are not flattened into a parallel comparison of any kind because they are true to life in their distinctness from each other, and also more concretely distinguished by gradations of class, age, sensibility, ideology, etc. So the contrivance of narrating 3 days in the lives of 3 women, all connected by Mrs. Dalloway, is a sort of convenient alternative to the truly messy and more existentially plausible interconnectivity that Woolf depicts in her novel. The difference between depicting one day for many different people, and three different days of three different people, is that in the latter case each day remains totally focalized through only one character, and thus, in a sense, each narrative in the film of The Hours is more or less self-centred. This is slightly mitigated in Cunningham’s novel by his rather skillful use of free indirect discourse, but the problem remains: three distinct episodes, however loosely connected, are fundamentally different from the multifaceted, quasi-Cubist representation of intersubjective reality Woolf achieved.

Cunningham’s novel notwithstanding, the film would have been far more interesting had it focused entirely on Clarissa Vaughan’s day, and thereby been an implicit rewriting of Mrs. Dalloway. Ultimately the whole 1951 section of the film comes to seem like an extended explanatory flashback, subordinated entirely to the fate of Richard in 2001. The revelation that Laura Brown abandoned her family instead of killing herself is supposed to have some explanatory power with regard to Richard’s character, but it has the effect of relegating that whole narrative to the status of a footnote, while also revealing how unmotivated was the choice of that one day in 1951, the birthday of Laura’s husband. If baking a birthday cake is the “trivial” event that causes Laura to break down, then for how many years has this “one” day been recurring? Why not focus on the day she left? We are told that she decided to leave on that day, but decisions are really made when they are enacted, so if her abandonment is the event that shapes the day in 2001, why not focus on that event? Clearly, Cunningham’s motivation was a desire to write three “ordinary” days that have buried or unrecognized subjective significance. As I’ve already described, the day he writes for Woolf does not hold up under scrutiny, and Clarissa Vaughan’s day is simply overloaded with incident, even before Richard kills himself. But if the day in 2001 is the true re-writing or re-enactment of Woolf’s novel, then Laura Brown, Mrs. Brown, has clearly been invented for the purpose of filling in the gap between 1923 and 2001—but arbitrarily so, since the novel itself is the only real connection between the three narratives. One wonders why Cunningham bothered to write the Woolf and Brown sections of his novel, since the last section is the one upon which the significance of the whole is made to rest. He might have made this episode at what he calls “the end of the twentieth century” into a novel in its own right, with the narratives of Woolf and Brown integrated in much the same way that Woolf integrates “backstory” into Mrs. Dalloway. Woolf somewhere writes something to the effect that she “dig[s] out beautiful caves behind [her] characters”; reading Cunningham’s novel, or watching the film, is a little like taking a tour of an abandoned mine that has been converted into a museum: made safe, lit too brightly, and reduced to an exemplary status it has not earned. All that’s missing is a gift shop.