Krasznahorkai Here Below

An introduction

It’s a big day for me. A writer I like won the Nobel, and I can feel securely smug about this because I already own all of his books and won’t have to compete with you, the curious newcomer, at the local shop. Unfortunately, I don’t have my books with me at present, so I can’t offer some choice quotations to you—but then again, if you’ll permit me to let myself off the hook, he is a hard writer to quote without quoting whole pages. If you really have the curiosity about László Krasznahorkai that I’ve just projected onto you, you are in the perfect position to begin reading him, because his fiction tends to be about people who are curious about, or impassioned with, or abidingly devoted to, or driven mad by art.

I will not try, here, to imitate his style, no, ladies and gentlemen, I will not be caught attempting some futile attempt at reproducing his hypotactic-paratactic prose, which has been not-entirely-erroneously likened to a “magma flow” or some other such brimstone simile, but I assure you, even if one were so foolish as to attempt to sully this great artist’s work with the aping paws of the hack mimic, they would find that their fraud fell on deaf ears, no one listening to their degraded copy any more than to the exalted original, we are surrounded by this nonsense, by imitators imitating imitations, positively drowning in this rubbish, and the buck, ladies and gentlemen, has to stop somewhere, the flow must be halted in its tracks, and the temptation to kitsch resisted, and (Okay, now I’m finished.)

I think one sincere way to introduce Krasznahorkai to prospective readers would be to tell you what some of his books are about, instead of droning on about his long sentences and other basic formal techniques. Make no mistake: his novels have content, and no, they are not “plotless fiction.” Things happen. Sátántangó is about a confidence-man, spiders, the death of a little girl, the sound of bells waking one up in the morning, rain and mud, dance and drink. It does not end well. I suspect it’s better than the seven-hour-long film, which I have not yet seen.

In English, we primarily know LK as the author of The Melancholy of Resistance, a forbidding and also desperately gripping, even thrilling panoramic account of the fall of a village to fascism, as witnessed by artist, holy fool, victim, murderer, and rat alike, along with perhaps death, or at least entropy, itself. But my favourite Krasznahorkai is the one who cultivates a fascination with the histories and cultures of what for him is “the East,” as first elaborated in A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East, a novella about the grandson of Prince Genji searching, outside of time, for a fabled garden rumoured to be somewhere in an exquisite and empty monastery outside of Kyoto. The narrator tells us in tenderly, breathlessly exhaustive detail how the monastery was built, from what wood, and how the wood was cut, and at what time of year, and so on. But this little story also captures, in a way Murakami never has, the wonderfully uncanny (or simply odd) sense one gets in Japan of moments in time separated by hundreds of years yet coexisting in some illusory way, as when, for instance, you buy a can of BOSS BLACK coffee from one of the vending machines that punctuate Krasznahorkai’s novella, and marvel at the small fact of its being heated for you by the machine, while you stare at a castle or shrine or just the winding streets themselves, or a heron, and see, and fail to see, time, as everyone else has for centuries.

Then there is his splendid fictionalized (?) travelogue of early-aughts China, Destruction and Sorrow Beneath the Heavens, which I’d especially recommend to North American fans of Jia Zhangke, because here the narrator, who presumably bears a strong resemblance to Krasznahorkai, spends most of his time touring China lamenting, bemoaning, and being generally annoying about the “destruction” of China’s cultural history, and the dearth of remaining historical sites, artefacts, etc. The conversations he has with Chinese artists and scholars are fascinating and entertaining little micro-dramas of the breakdown of cultural “exchange,” and if we come away from this book with the sense that Krasznahorkai only truly cares about a quasi-mythical China of the past that only exists, for him, in books, we also may have the sense that he is expressing here a disappointment that one in China cannot entertain for long because it is simply so un-pragmatic, so backward-looking, so fraught with the history of humiliation, and so large: too literary to be progressive, in the general sense of moving forward. Krasznahorkai wants to pause time and knows he cannot.

To my mind, his masterpiece is Seiobo There Below, which you can think of as being a novelist’s answer to Pound’s Cantos. Like Pound, Krasznahorkai demonstrates here—through discrete chapters each of which describes in detail, or narrates an encounter with, some more or less familiar masterpiece of art or of natural beauty, such as the Alhambra, or Andrei Rublev’s Trinity, or the Ise Shrine, or the work of Pietro Perugino, or a heron standing in a river, for a moment, seen by no one—the point of this is, as I’m suggesting, to demonstrate Krasznahorkai’s idiosyncratic canon of the world’s culture, as Pound fitfully attempted before him. But while one probably comes away from Pound’s project with a few beautiful phrases or lines guiltily stashed in one’s pockets like the loot of a pickpocket, one comes away from Krasznahorkai’s novelistic Noh drama with the warm, if estranging sense of having read some of the most exquisite and moving short stories ever written. I cannot even think about the story in which a man thinks he sees a painting of Christ move without pausing and silently, inwardly gasping at it all over again.

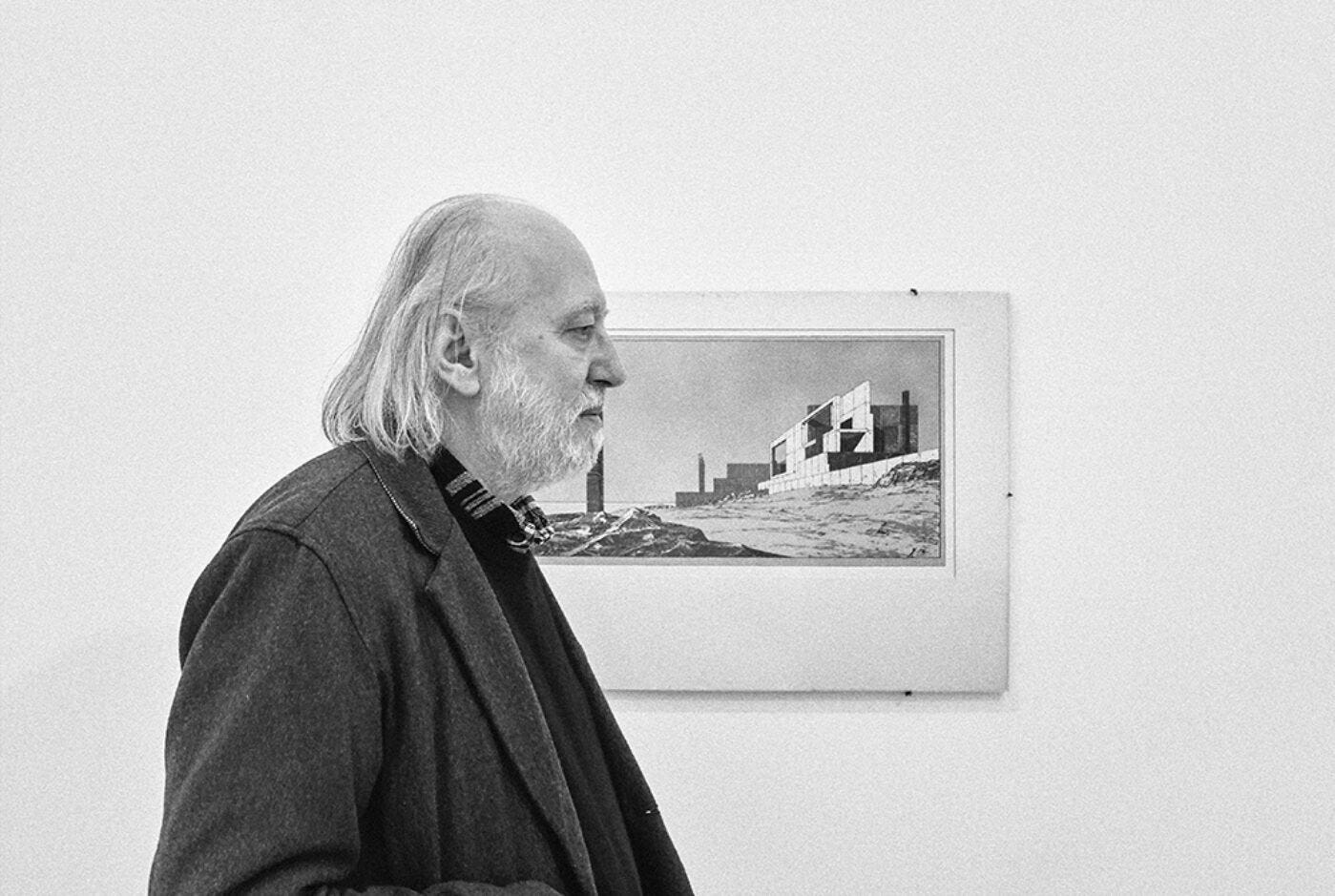

I can also recommend, to those who enjoy writers writing about writers and artists, the novella Spadework for a Palace, which is about a librarian obsessed with Herman Melville, Malcolm Lowry, and Lebbeus Woods. There’s also a lovely sort of art book, The Manhattan Project, which is about LK writing this novella in New York, also the setting of his earlier novel War and War, which I have been saving for a rainy day. The other novellas—The Last Wolf, Animalinside, and Chasing Homer—are always said to be monologues on terror, bestiality and barbarism, which they are, but they are also quite funny, sometimes at exactly the moment they are most chilling. If I spoiled the punchline of Chasing Homer for you, you might never forgive me. Just pick one of these books I’ve described and run with it, and hope that unlike so many of LK’s narrators and characters, you won’t be running for your life. But who can say how much depends upon a novel? Maybe reading one of his books will remind you of what you should be running, sprinting, fleeing in panic, scurrying, hurrying, dashing, moving towards—even if you never reach it. There is beauty, but not for us. Chase it anyway, he seems to say.

I lied. I can give you one passage, one I copied out some time ago, to take away with you, from Seiobo, like a jewel that melts when you aren’t looking:

Everything around it moves, as if just this one time and one time only, as if the message of Heraclitus has arrived here through some deep current, from the distance of an entire universe, in spite of all the senseless obstacles, because the water moves, it flows, it arrives, and cascades; now and then the silken breeze sways, the mountains quiver in the scourging heat, but this heat itself also moves, trembles, and vibrates in the land, as do the tall scattered grass-islands, the grass, blade by blade, in the riverbed; each individual shallow wave, as it falls, tumbles over the low weirs, and then, every inconceivable fleeting element of this subsiding wave, and all the individual glitterings of light flashing on the surface of this fleeting element, this surface suddenly emerging and just as quickly collapsing, with its drops of light dying down, scintillating, and then reeling in all directions, inexpressible in words

god i love your writing

So exciting. I love LK sm and can’t wait to read more of his novellas